Review! That! Book! DHALGREN by Samuel R. Delaney, Part 1

Posted: November 14, 2019 Filed under: Book Review, Uncategorized | Tags: dhalgren, fantasy, magic realism, magical realism, samuel delaney, samuel r delaney, science fiction Leave a commentReviewing Dhalgren is going to be a thing. When I say a thing, I mean that it’s going to take several posts to cover this baby. It may be the most significant and problematic piece of science fiction I’ve ever read. I’m going to address it in chunks based on its many themes. If you’re here for a graduate-level thesis on this graduate-level book, you’re in the wrong place. I am but a humble librarian/writer/book person, and these thoughts are the best that my humble librarian/writer/book person brain can produce. That said, if you are at my level, this might be useful to you. If nothing else, we can console each other now that this monster book has ripped out our egos.

A few notes first.

- I will not be using racial slurs. Dhalgren uses the N-word very liberally and actually expanded my vocabulary somewhat as far as other racist language goes. I’m not sure how I feel about this. On one hand, it’s good that I know. On the other, I feel uncomfortable with that knowledge. I didn’t like hearing the N-word so much and I think that was the reason that the author made that choice. I will attempt to discuss race in the context of this book, and I will do so to the best of my Italian-Irish-Plain-White-Bread-American abilites, but I won’t be using those words.

- Speaking of, I’m going to screw up the conversation about race. How could I not? I’ve never lived a Black life and while I can do my best to understand, I’m positive that there are things about Blackness and the Black experience that will remain beyond me no matter how much Ta-Nahesi Coates I read. That goes triple for this particular title, which was written 50 years ago by a Black man. I’m going to do my best because ignoring race in this book would be a disservice to it; as in broader American society, race in Bellona is inextricable from all of its other issues. If you feel like calling me out when I screw up, I encourage you to do so. If you’d rather not educate me, but still want to read my review, race will have its own subheading so you’ll have a heads-up to handle that section however you consider appropriate.

- I am not going to get this “right.” If you have opinions about DHALGREN that differ from mine, great. There’s a comments section. Have at it! But unless you’re Samuel R. Delaney, know that I don’t believe you’re going to get it “right” either. I don’t think correctness applies to this particular work. If you are Samuel R. Delaney, then I’m truly sorry for the mess I’m about to make of your incredible book.

If you haven’t read the book yet, there are also a few things you’re going to need to know about before we delve in.

- An orchid is a type of handheld weapon unique to Bellona. Think of a flower made of metal that you wear like a mitten. Failing that, think of a cage around your hand with sharp points poking out.

- Bellona is one of the twelve largest cities in the U.S. and is probably located somewhere in Kansas.

- Many people in Bellona acquire and wear optical chains, which are long lengths of brass chain set with mirrors and pieces of glass. The experience of acquiring them is usually traumatic. They cannot be bought or taken by force, but can be removed from a dead body.

- The Scorpions are a loose gang. They’re intimidating and sometimes dangerous.

That’s nowhere near all the background that you need to know, but it’s the best I can do without turning this piece into a listicle. Let’s forge ahead anyway. To Bellona!

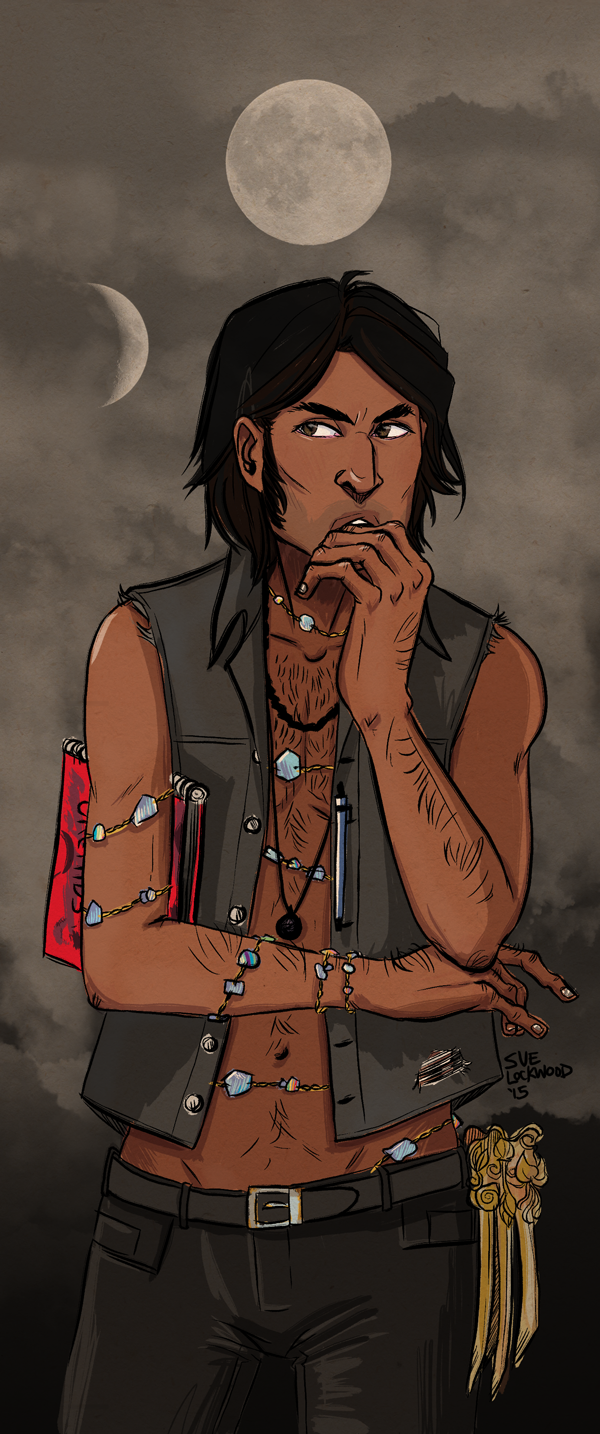

Incredible DHALGREN art from Art By-Products

Perception

I was originally going to call this section Mental Health, but that doesn’t begin to encompass the subject. In Bellona, the division between mind and reality is perilously blurry and it is not at all clear which one affects the other more.

The Kid has a history of mental health problems, and nothing frightens him more than the possibility of a relapse. Of all the places in the world that he could have ended up, this city of shifting realities is probably the worst. And the best, maybe. There seem to be holes in time in Bellona, and when we first discover this, they’re presented as holes in the Kid’s memory. This kicks off Kid’s self-perpetuating anxiety about whether or not he is crazy or will return to a state where he has no awareness of what he’s doing.

But Kid’s mental health problems predate Bellona, so we know that they don’t proceed from there. His loss of his real name and habit of wearing one shoe are both artifacts from the wider world – the one he fit into so poorly. In Bellona, he receives validation from his girlfriend, Lanya, that he’s lost considerable chunks of time. But has he? Lanya later admits that there are hours of her own for which she can’t account. Fires that should consume the city in days continue unabated for weeks, and certain food stores appear to restock themselves as though trapped in a loop. Couple that with the episodic nature of DHALGREN and you have the makings of a place that’s profoundly unmoored in time. It begs the question of how people narrate their lives when reality itself isn’t certain.

From POV-Ray

It also suggests that nothing happening in Bellona is real. But there are things that happen there, like the appearance of the Kid’s debut poetry collection, BRASS ORCHIDS, that must have some relationship to the wider world. People come in, too, so someone must be reporting across the bridge. Bellona is tethered to reality, at least, and throughout the book, the Kid’s biggest concerns seem to revolve around maintaining that tether in at least an operative sense. He gets a job even though nobody uses money. He joins a gang even though he doesn’t need protection. He publishes a book of poetry even though he’s not sure he wants to be a poet. He can’t just be. If he resorted to that, he’d have no continuity at all and no way to mark either time or his own significance in it. He’d have no way of knowing if he really were crazy or not. Sanity is the perception of purpose, a self-delusion that’s necessary for measuring, and therefore adequately observing, life.

The way you look at something really can affect its state. Consider subatomic particles that must be waves and particles…until they’re observed. These little specks are unknowable, mutable as Bellona itself. To perceive them is to fix them in a definable space, but only as long as you are actively watching. Bellona is the same way, and to a great extent, so are the people who live there.

And you thought this wasn’t real science fiction!

Whether the Kid’s existence itself matters depends on how he agrees to perceive reality. Whether in poetry or in action, he’s always got to move. Moreover, he’s got to move in the perceptions of others or he seems to disappear, or at least move to a state where he has no self-awareness or control over his actions. His biggest, most frightening loss of time happens when he’s sleeping in the open with Lanya and not doing much. She leaves, and when she comes back, he’s gone. For the Kid’s part, he perceives himself waking up and immediately heading to a Scorpion raid, after which he’s increasingly in the company of a large crowd of fellow gang members. Their observation of him seems to prevent more large lapses, but prior to that, when he loses Lanya, she reports that he’s been active for days outside of her perception.

The critical point here is that the Kid can’t observe himself reliably, even to the extent that he can remain self-aware. He needs to see himself being observed by others, and through their eyes, know he is real. His book’s popularity in particular appears to ground him, despite his ambivalence about being a poet.

Everything in Bellona seems to be a charm against lack of perception. Otherwise pointless baubles like the optical chains and the light shields exist to alter and enhance the wearer’s presentation to the world. The Scorpions maintain their fearsome reputation by smashing stuff up, but there are no rival gangs to intimidate and they rarely accomplish anything notable. Nevertheless, Calkin’s paper (which prints a different random date every day) reports on them. It makes them famous, just as Calkin makes the Kid famous by printing his book.

From “Dhalgren Sunrise,” a multimedia adaptation, created by Mitchel K. Ahern. Image from Patch

We almost never see Calkin. Isn’t that interesting? Everyone is highly aware of him because of the paper, his mansion, his parties, his power. He is the man with all the words and the power to control what others know about their local luminaries. All Bellona seems to know what the Kid is up to all the time, presumably because they’re reading it in the paper, but the Kid himself is increasingly flummoxed by that effect as the book progresses. His self-perception comes through Lanya, Denny, the Scorpions. It’s unclear how the perception of others affects the Kid’s state of awareness. With Calkin’s publication and very wide distribution of the Kid’s book, not to mention his control of the narrative of Kid’s publicity, it would stand to reason that Calkin gains a measure of control over the Kid’s identity too. People certainly treat the Kid with more respect once he becomes a news item and artiste, even though most of them only read his poems to see if he wrote anything about them.

Like the Kid, the other Bellonans need to be perceived to be real. But not all of them are perceived. Even Lanya seems to fall into existential holes now and then.

This effect doesn’t just extend to people. Things that everyone agrees upon seem to have the strongest presence as reality. Effects like the double moon and the enormous sun are observed in concert, their details becoming hazy when reported on an individual level. The fear and wonder that they inspire may be the fuel that keeps Bellona aware. Once the second moon appears, everyone shares the experience of checking for it, naming it after George, discussing it. The giant sun inspires the universally shared experience of terror and fatalism. These are critical pins of the Bellona experience. Without them, who’s to say that the city itself would remain a distinct entity? If Bellona were a person, these would be its performances, its attempts to cling to reality by remaining remarkable.

Calkin immolates his own power when he enters the monastery near the end of the book. Immediately, Bellona experiences a spike in unpredictability. People get separated, fires worsen, and formerly powerful interpersonal ties break. Is this what happens when the person narrating the barely-real city stops holding it together with his words? Very possibly. This, too, is the moment when the Kid and some of his friends flee the city in an unplanned escape from the worsening fires and chaos.

And then, of course, the prose loops. The Kid’s exit parrots the exact dialogue from his entrance, only when he leaves, he himself takes on the role of the departing Bellonans. Makes you wonder if there will be another Calkins for the newcomer. How specific to the Kid was his experience? How much of Bellona did he personally observe into existence? His departure could be read in several different ways now, depending on how relatively unstable we think reality is in the city.

Illustration by DeathBearBrown

If the Kid’s perception influenced Bellona even a little, then his departure could be read as a state of mind, but even this leaves us with questions. Did Bellona become untenable when the Kid stopped perceiving it as a tolerable place to live, or did he finally lose sight of himself as an entity who made sense in Bellona’s context? His flight of self-preservation might have been more than an escape from fire. Without something to do in Bellona – something to be in Bellona – the Kid could very well be lost to literal obscurity. Did he lose the ability to control his awareness of the city with his art and actions? Conversely, did the city’s chaos naturally strip meaning from whatever agency the Kid ever had to alter his life with its greater shenanigans and vapidity of purpose? If our lives take on the meaning that we choose for them, then a place with yawning holes in time and physical properties that defy the laws of space and time would tend to defy our attempts to put our personal entropy in order. It’s hard to imagine anyone thriving that way for long.

Personally, I think the answer to the puzzle of perception and Bellona is intricately tied up with how Bellona’s residents relate to creativity. But it’s been 2200 words and I’m out of Dhalgren-related graphics for today. Tune in tomorrow for our next section: ART.